NIX Guts

Topics - NIX Guts

Why Linux? Free, Portable, Almost Crashless, Secure, Scalable, Debugging. Why not Linux? Distro-fatigue, Learning Curve, Sustainability of fragmented tools.

Editor Note:

- The material below was cobbled together for personal use, from attributed sources, and endured some mild look/feel massage.

- Document Purpose: Conveniently scoped refresher on the listed Linux OS components.

Sources:

- The Art of Unix Programming, The Linux Information Project

- TLDPThe Linux Documentation Project

- System Call - Wikipedia

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

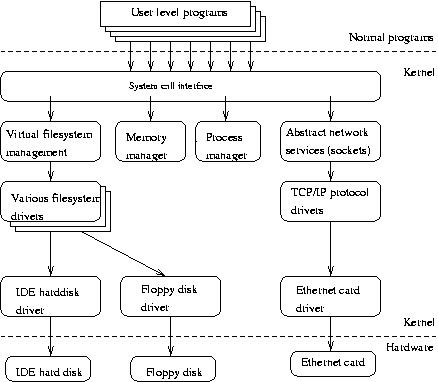

Kernel

- The Linux kernel consists of several important parts.

- Process management - creates processes, and implements multitasking by switching the active process on the processor.

- Memory management - takes care of assigning memory areas and swap space areas to processes, parts of the kernel, and for the buffer cache.

- Hardware device drivers

- At the lowest level, the kernel contains a hardware device driver for each kind of hardware it supports.

- Since the world is full of different kinds of hardware, the number of hardware device drivers is large.

- There are often many otherwise similar pieces of hardware that differ in how they are controlled by software.

- The similarities make it possible to have general classes of drivers that support similar operations;

- each member of the class has the same interface to the rest of the kernel but differs in what it needs to do to implement them.

- For example, all disk drivers look alike to the rest of the kernel, i.e., they all have operations like ‘initialize the drive’, ‘read sector N’, and ‘write sector N’.

- Filesystem drivers

- The virtual filesystem (VFS) layer that abstracts the filesystem operations away from their implementation.

- Each filesystem type provides an implementation of each filesystem operation.

- When some entity tries to use a filesystem, the request goes via the VFS, which routes the request to the proper filesystem driver.

- Network management

- The various network protocols have been abstracted into one programming interface, the BSD socket library.

- and various other bits and pieces

Important Core Services

- Init

- The single most important service in a UNIX system is provided by init init is started as the first process of every UNIX system, as the last thing the kernel does when it boots.

- When init starts, it continues the boot process by doing various startup chores (checking and mounting filesystems, starting daemons, etc).

- The exact list of things that init does depends on which flavor it is; there are several to choose from.

- init usually provides the concept of single user mode, in which no one can log in and root uses a shell at the console; the usual mode is called multiuser mode.

- Some flavors generalize this as run levels; single and multiuser modes are considered to be two run levels, and there can be additional ones as well, for example, to run X on the console.

- Linux allows for up to 10 runlevels, 0-9, but usually only some of these are defined by default.

- Runlevel 0 is defined as ‘system halt’.

- Runlevel 1 is defined as ‘single user mode.

- Runlevel 3 is defined as ‘multi user’ because it is the runlevel that the system boot into under normal day to day conditions.

- Runlevel 5 is typically the same as 3 except that a GUI gets started also.

- Runlevel 6 is defined as ‘system reboot.

- Other runlevels are dependent on how your particular distribution has defined them, and they vary significantly between distributions.

- Looking at the contents of /etc/inittab usually will give some hint what the predefined runlevels are and what they have been defined as.

- In normal operation, init makes sure getty is working (to allow users to log in) and to adopt orphan processes (processes whose parent has died; in UNIX all processes must be in a single tree, so orphans must be adopted).

- When the system is shut down, it is init that is in charge of killing all other processes, unmounting all filesystems and stopping the processor, along with anything else it has been configured to do.

- Terminal Logins

- Logins from terminals (via serial lines) and the console (when not running X) are provided by the getty program. init starts a separate instance of getty for each terminal upon which logins are to be allowed.

- getty reads the username and runs the loginprogram, which reads the password.

- If the username and password are correct, login runs the shell.

- When the shell terminates, i.e., the user logs out, or when login terminated because the username and password didn’t match, init notices this and starts a new instance of getty.

- The kernel has no notion of logins, this is all handled by the system programs.

- Syslog

- Periodic Execution (cront/at)

- GUI/X

- UNIX and Linux don’t incorporate the user interface into the kernel; instead, they let it be implemented by user level programs.

- This applies for both text mode and graphical environments.

- Networking

- Network Logins

- Network File Systems

- Printing

- File System

System Calls

In computing, a system call is the programmatic way in which a computer program requests a service from the kernel of the operating system it is executed on. -wikipedia

- When accessing the above system services, an application makes a system call.

- They are the way an application “enters the kernel” to do work.

- Privilege rings

- Summary:

- 0 is the kernel/executive

- Device driver activity at 1/2

- 3 is for applications

- The architecture of most modern processors, with the exception of some embedded systems, involves a security model.

- For example, the rings model specifies multiple privilege levels under which software may be executed: a program is usually limited to its own address space so that it cannot access or modify other running programs or the operating system itself, and is usually prevented from directly manipulating hardware devices (e.g. the frame buffer or network devices).

- Normal applications obviously need access to these components, so system calls are made available by the operating system to provide well-defined, safe implementations for such operations.

- The operating system executes at the highest level of privilege, and allows applications to request services via system calls, which are often initiated via interrupts.

- Any resource available at level n is also available at 0-n.

- Summary:

- Interrupt

- Interrupt kernel (via event) to ask for a call to run a call.

- Categories

- Process Control

- load, execute, end, abort, create process (ie fork), terminate process, get/set process attributes, wait for time, wait event, signal event, allocate, free memory

- File Management

- create file, delete file, open, close, read, write, reposition, get/set file attributes

- Device Management

- request device, release device, read, write, reposition, get/set device attributes, logically attach or detach devices

- Information Maintenance

- get/set time or date, get/set system data, get/set process, file, or device attributes

- Communication

- create, delete communication connection, send, receive messages, transfer status information, attach or detach remote devices

Libraries

- Generally, systems provide a library or API that sits between normal programs and the operating system.

- On Unix-like systems, that API is usually part of an implementation of the C library (libc), such as glibc, that provides wrapper functions for the system calls, often named the same as the system calls they invoke.

- The library’s wrapper functions expose an ordinary function calling convention (a subroutine call on the assembly level) for using the system call, as well as making the system call more modular.

- Here, the primary function of the wrapper is to place all the arguments to be passed to the system call in the appropriate processor registers (and maybe on the call stack as well), and also setting a unique system call number for the kernel to call.

- In this way the library, which exists between the OS and the application, increases portability.

Memory Management

A Swedish drinking song, (rough) translation: `Memory, I have lost my memory. Am I Swedish or Finnish? I can’t remember TLDP

- Note: A note on operating system terminology: computer science usually distinguishes between swapping (writing the whole process out to swap space) and paging (writing only fixed size parts, usually a few kilobytes, at a time).

- Paging is usually more efficient, and that’s what Linux does, but traditional Linux terminology talks about swapping anyway.

- Virtual Memory

- Linux supports virtual memory, that is, using a disk as an extension of RAM so that the effective size of usable memory grows correspondingly.

- The kernel will write the contents of a currently unused block of memory to the hard disk so that the memory can be used for another purpose.

- When the original contents are needed again, they are read back into memory.

- Swap Space

- Creating/Sharing

- Buffer Cache

- Reading from a disk is very slow compared to accessing (real) memory.

- In addition, it is common to read the same part of a disk several times during relatively short periods of time.

- For example, one might first read an e-mail message, then read the letter into an editor when replying to it, then make the mail program read it again when copying it to a folder.

- Or, consider how often the command ls might be run on a system with many users.

- By reading the information from disk only once and then keeping it in memory until no longer needed, one can speed up all but the first read. This is called disk buffering, and the memory used for the purpose is called the buffer cache.

File System

“On a UNIX system, everything is a file; if something is not a file, it is a process.”

- Layout of a Linux file system

- Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

- Partitions

- Data partition: normal Linux system data, including the root partition containing all the data to start up and run the system; and

- Swap partition: expansion of the computer’s physical memory, extra memory on hard disk.

- The kernel is on a separate partition as well in many distributions, because it is the most important file of your system.

- If this is the case, you will find that you also have a /boot partition, holding your kernel(s) and accompanying data files.

- The rest of the hard disk(s) is generally divided in data partitions, although it may be that all of the non-system critical data resides on one partition, for example when you perform a standard workstation installation.

- When non-critical data is separated on different partitions, it usually happens following a set pattern:

- a partition for user programs (/usr)

- a partition containing the users’ personal data (/home)

- a partition to store temporary data like print- and mail-queues (/var)

- a partition for third party and extra software (/opt)

- Directories: files that are lists of other files.

- Special files: the mechanism used for input and output. Most special files are in /dev, we will discuss them later.

- Links: a system to make a file or directory visible in multiple parts of the system’s file tree. We will talk about links in detail.

- (Domain) sockets: a special file type, similar to TCP/IP sockets, providing inter-process networking protected by the file system’s access control.

- Named pipes: act more or less like sockets and form a way for processes to communicate with each other, without using network socket semantics.

- Display and set paths

- Describe the most important files, including kernel and shell

- Find lost and hidden files

- CRUD

- Files and Directories

- Permissions

- Display contents of files

- Understand and use different link types

Client-server protocols

- A protocol tells us how to talk

- Standard protocols usually have RFC, ex: ftp, telnet, http.

- Telnet is an example.

Shell

“the shell is the steering wheel of the car”

- A shell can best be compared with a way of talking to the computer, a language. Most users do know that other language, the point-and-click language of the desktop. But in that language the computer is leading the conversation, while the user has the passive role of picking tasks from the ones presented.

- It is very difficult for a programmer to include all options and possible uses of a command in the GUI-format. Thus, GUIs are almost always less capable than the command or commands that form the backend.

- The shell, on the other hand, is an advanced way of communicating with the system, because it allows for two-way conversation and taking initiative. Both partners in the communication are equal, so new ideas can be tested.

- The shell allows the user to handle a system in a very flexible way. An additional asset is that the shell allows for task automation.